“The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me; my eye and God’s eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, one love.” – Meister Eckhart

“Which God?” my mother cynically responded, “the God of the Jews? Jesus? Allah?” I remember being confused by the question. “There is only one,” I replied.

I was ten years old at the time, and the intent behind answering my mother’s question as I did was not to affirm that only one of these “Gods” was the real deal and the others imposters. I remember thinking it odd that I should be asked a question about God that turned religion into something like the once popular To Tell the Truth game show. In that show individuals had to pick out a person believed to match a given description of a person with a particular occupation or life experience. The challenge was that the target had to be identified from among a group of imposters who could present themselves as the real deal. As a ten-year-old boy, my modal intuitions (i.e., my intuitions about possibility and necessity) were not as refined as they would become three decades later, but even at that age I knew that God was supposed to be the greatest possible being, and I was quite sure that there could not be more than one such being. But I also thought that surely that sort of being, a being with great and unsurpassed power and knowledge, could manifest itself in many different forms.

From whence came this idea of God? Some theologians and philosophers have said that belief in God is innate to the human mind. The Protestant reformer John Calvin spoke of a sensus divinitatis (sense of divinity), an innate human disposition to form belief in some kind of god. But it’s likely that my own environment played an at least equally important role in shaping my childhood convictions. While my parents were not religious, my grandmother was very much so. She gave me my first Bible, the Children’s Living Bible, but she was far from sectarian in her religious views. Her bookshelves were lined with a broad range of books on religion and spirituality, from evangelical Christianity to various books on parapsychology, theosophy, and eastern spirituality. It wouldn’t be surprising to find her reading Billy Graham and Edgar Cayce on the same day. So while my earliest encounter with religion had a broadly Christian theological core, it was an encounter with a diversity of religious and philosophical viewpoints. My earliest impression, though, was that these different voices were complementary rather than competing.

Teenage Years: From the Occult to Christianity

After my grandmother’s death during my early teens, I took a deeper interest in religion, mainly esoteric religions and the occult. My dad’s agnosticism did not prevent him from accumulating a large number of books on the paranormal and the occult. I read them with great fascination. But by the middle of high school my interest in the occult had dissipated and was replaced with a more serious engagement with Christianity. My intellectual curiosity about occult practices and the paranormal gave way to a desire to know and live for God in a more meaningful way. Increased feelings of separation from God and an inner emptiness intensified this desire, and it led me to a daily reading of the Bible. During this time something emerged in my individual psychology that would have a lasting impact on me: the ability to experience God through text and nature.

My regular reading of the Bible brought God more and more into my consciousness life, yet not always in a positive way, especially at the beginning, for the Bible introduced me to the darker side of human nature and myself, which often triggered deep feelings of guilt. I was very much as St. Augustine described himself in his work the Confessions, a divided self laboring under the guilt of sin. I wanted to love and serve God, but I was deeply conscious of my inadequacies in doing so. However, the more I read from the gospels and immersed my consciousness in the narratives of Christ’s person and redemptive work, especially the Gospel according to John, I was often overwhelmed with a sense of the love of God.

This developing sense of God’s love and forgiveness reached a climax in a very powerful experience of God on a summer evening shortly after graduating from high school in 1984. I was sitting on the roof of my parent’s house, as I often did, but this time my attention was drawn to the starry night sky, which was particularly clear that night. I looked up and was overwhelmed by the vastness of the sky and the seemingly infinite number of stars. I felt incredibly small and alone, but immediately I felt an amazing expansion in my own consciousness, centered specifically on my relationship to God through Christ. Christ’s words entered me: “I am the resurrection and the life. He who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and whoever lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” (John 11:25-26). I had already believed, but the question was as fresh as ever, as if I had never heard these words before, and I felt like the words were personally directed to me. And in this moment, I believed in a way that felt like an unprecedented surrender. Immediately I felt the presence of God, loving, forgiving, and healing my hitherto deeply divided self. The emptiness was gone.

Although my early journey to the Christian faith began with involvement in the charismatic movement while I was a senior in high school, after my summer experience of God I quickly moved towards more traditional Protestant theology, first joining the Christian Reformed Church and then a Calvinistic Baptist church. It was during this time that I experienced a wonderful growth in my spiritual life over the span of a few years, experiencing a deepening of my faith in Christ. My earlier intellectual curiosity also re-emerged but with a focus on Christian theology. After first learning Koine Greek so I could read the New Testament in its original language, I embarked upon pastorally directed theological studies at the Calvinistic Baptist church I had joined, an affiliation I kept for many years. My interest in philosophy grew out of this formative period of theological study, specifically the interests in logic and epistemology that would characterize the early phase of my subsequent academic career as a Christian philosopher. My budding philosophical interests inspired me to embark upon my college education and major in philosophy. By 1989, after two years at a junior college, I found myself immersed in a very rigorous and intellectual rewarding undergraduate philosophy program at Santa Clara University.

Although my early journey to the Christian faith began with involvement in the charismatic movement while I was a senior in high school, after my summer experience of God I quickly moved towards more traditional Protestant theology, first joining the Christian Reformed Church and then a Calvinistic Baptist church. It was during this time that I experienced a wonderful growth in my spiritual life over the span of a few years, experiencing a deepening of my faith in Christ. My earlier intellectual curiosity also re-emerged but with a focus on Christian theology. After first learning Koine Greek so I could read the New Testament in its original language, I embarked upon pastorally directed theological studies at the Calvinistic Baptist church I had joined, an affiliation I kept for many years. My interest in philosophy grew out of this formative period of theological study, specifically the interests in logic and epistemology that would characterize the early phase of my subsequent academic career as a Christian philosopher. My budding philosophical interests inspired me to embark upon my college education and major in philosophy. By 1989, after two years at a junior college, I found myself immersed in a very rigorous and intellectual rewarding undergraduate philosophy program at Santa Clara University.

The Movement Towards Christian Inclusivism

![]() Although I had aligned myself with the historic Protestant Christian tradition, my learning experience at Santa Clara University (a Jesuit university) introduced to me the wisdom of the Catholic tradition. I developed a great interest in and appreciation for St. Thomas Aquinas, an admiration that has continued to this day. My theological perspective was further broadened during my four years in graduate school, at the University of Oxford and also my year as a visiting fellow at the University of Notre Dame. My educational experience, both in the classroom and in my personal interactions and relationships with faculty and fellow students, helped cultivate in me a respect for Christian traditions other than my own. From this respect emerged a considerably more inclusivist attitude towards Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and various non-calvinistic Protestant traditions. My religious inclusivism developed even further during my five years as a professor in the Philosophy Department at Saint Michael’s College, where I had the wonderful experience of teaching in a Catholic institution and cultivating deeply meaningful friendships with several Catholic colleagues. I saw us as adherents of a common faith understood in different ways. And that’s what inclusivism fundamentally meant for me at this time. Christians in these other traditions were genuine Christians, many of whom had cultivated a deeper level of spirituality than I observed among my fellow Calvinists, and I could acquire a deeper appreciation of my relationship to God through their insights and practices. Inclusivism enhanced my own spiritual development.

Although I had aligned myself with the historic Protestant Christian tradition, my learning experience at Santa Clara University (a Jesuit university) introduced to me the wisdom of the Catholic tradition. I developed a great interest in and appreciation for St. Thomas Aquinas, an admiration that has continued to this day. My theological perspective was further broadened during my four years in graduate school, at the University of Oxford and also my year as a visiting fellow at the University of Notre Dame. My educational experience, both in the classroom and in my personal interactions and relationships with faculty and fellow students, helped cultivate in me a respect for Christian traditions other than my own. From this respect emerged a considerably more inclusivist attitude towards Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and various non-calvinistic Protestant traditions. My religious inclusivism developed even further during my five years as a professor in the Philosophy Department at Saint Michael’s College, where I had the wonderful experience of teaching in a Catholic institution and cultivating deeply meaningful friendships with several Catholic colleagues. I saw us as adherents of a common faith understood in different ways. And that’s what inclusivism fundamentally meant for me at this time. Christians in these other traditions were genuine Christians, many of whom had cultivated a deeper level of spirituality than I observed among my fellow Calvinists, and I could acquire a deeper appreciation of my relationship to God through their insights and practices. Inclusivism enhanced my own spiritual development.

My movement into Christian inclusivism was partially responsible for my eventual departure from the Calvinistic Baptist tradition around 2004, after 18 years of affiliation with this tradition. The movement was gradual and actually began shortly after attending Santa Clara University. While fellow church members “tolerated” my attending a Catholic university (primarily because I had the pastor’s support), criticisms mounted while I was in graduate school. Many of my fellow church members were suspicious of my course of study. They were, like most of the Calvinistic Baptists I have met over the years, clearly not fans of philosophy. But there’s at least one thing worse than philosophy, and that’s Roman Catholicism. Indeed, I was often under the impression that some Calvinistic Baptists hated philosophy because it was something Catholics did so well. My increasing positive appraisal of different aspects of Catholic theology and enthusiasm for the work of St. Thomas Aquinas intensified “concerns” about the “spiritual effects” of my education, and these concerns eventually evolved into frequent vicious criticisms that served only to alienate me from this particular theological tradition.

It’s worth noting that the unpleasant dynamics of rigid Christian exclusivism I experienced among Calvinistic Baptists were not a mere local phenomenon. I found more of the same, and sometimes worse, intolerance and narrow-mindedness towards Catholicism and other forms of Christianity in at least six different Calvinistic Baptist churches I attended between graduate school and the first five years of my teaching career. The lack of respect for philosophical inquiry, rigid exclusivism grounded in a highly parochial conception of Christianity, distaste for self criticism, and a moral outlook and practical theology that was intractably stuck in a perpetual time warp, circa 18th century New England, each contradicted many of the intuitions forged through my own spiritual experiences and intellectual reflections. These each alienated me from participating in the life of the tradition, which I terminated around 2004.

The Journey to India

A bolder venture into inclusivism developed after 2004 when my Christian inclusivism evolved into an inclusivism of world religions. The regular teaching of courses in world religions, the nature of religious experience, and philosophy of religion at this point in my career provided me with an opportunity to dig deep into eastern philosophy and religious practices. This exploration resulted in my growing appreciation of eastern approaches to God, as well as an assimilation of aspects of eastern thought to my own developing philosophy of religion. Never personally detached from matters of intellectual interest, my attraction to eastern spirituality eventually manifested in my own spiritual experiences and practices, which became increasingly oriented towards the mystical and philosophical heritage of the devotional or bhakti traditions of India.

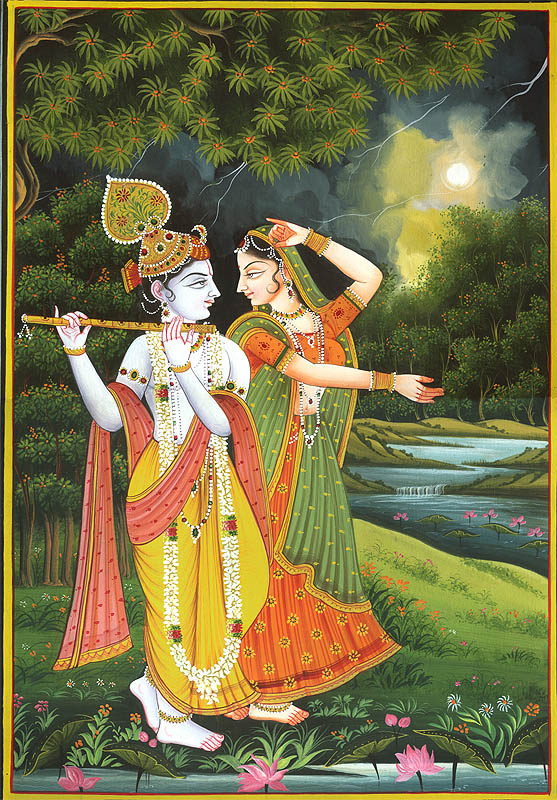

In 2011 I converted to Gaudiya Vaishnavism (also known as Bengali Vaishnavism), an eastern stream of devotional theism that may be traced to the teachings of Caitanya Mahaprabhu in sixteenth-century Bengal and the sacred Vedas of ancient India. On its philosophical axis, Gaudiya Vaishnavism is a school of Vedanta, which seeks to systematically elaborate the teachings of the Upanishads, Brahma Sutras, and Bhagavad Gita –principal sacred texts of the Indic traditions. On its religious axis, Gaudiya Vaishnavism is a monotheistic mystical tradition centered on bhakti (love and devotional service) to Krishna as the Supreme Personality of the Godhead.

In 2011 I converted to Gaudiya Vaishnavism (also known as Bengali Vaishnavism), an eastern stream of devotional theism that may be traced to the teachings of Caitanya Mahaprabhu in sixteenth-century Bengal and the sacred Vedas of ancient India. On its philosophical axis, Gaudiya Vaishnavism is a school of Vedanta, which seeks to systematically elaborate the teachings of the Upanishads, Brahma Sutras, and Bhagavad Gita –principal sacred texts of the Indic traditions. On its religious axis, Gaudiya Vaishnavism is a monotheistic mystical tradition centered on bhakti (love and devotional service) to Krishna as the Supreme Personality of the Godhead.

My conversion to Gaudiya Vaishnavism gradually emerged over a three-year period as the result of major shifts in my religious and philosophical perspective that were facilitated in part by my more mature reflections on core questions in the philosophy of religion, my deeper engagement with Vedanta philosophy, and my study and teaching of the Bhagavad Gita, one of the great sacred texts of eastern philosophy and spirituality. My inclusivist attitude helped remove obstacles to understanding other traditions and inspired the pursuit of the wisdom contained in those traditions, but ultimately it was only one element among a variety of interrelated philosophical and experiential factors that led me to the wisdom of India.

After a near fatal automobile accident in March 2011, I experienced a deep personal transformation that drew me closer to the teachings and spiritual practices of the Gaudiya tradition. My associations with Swami Tripurari Maharaja and the devotees at Audarya (the Vaishnava ashram in northern California) provided me with a unique opportunity to more authentically explore the philosophical and spiritual tradition of Gaudiya Vaishnavism. Most importantly, it served as a catalyst for my own experience of Krishna consciousness, which brought profound clarity to different aspects of my personal life and spiritual journey. Already long convinced on philosophical grounds that God may be experienced in different ways through diverse spiritual practices and traditions, each yielding its particular form of spiritual attainment and relation to God, I see my movement eastward as the natural development of my personal devotion to God that began in the summer of 1984. It’s not surprising that devotion should be dynamic and evolve in a way that reflects changes in our psychological dispositions, aesthetic sensibilities, and intellectual outlook.

Now, 37 years later, I reflect on that brief exchange with my mother when I was a young boy. “Which God?” my mother cynically responded, “the God of the Jews? Jesus? Allah?” “There is only one,” I replied. I believe the intuition back then was correct. There is only one Absolute being. Indeed, there are philosophical reasons for supposing that there could not be more than one Absolute being. What I know now theoretically and experientially, and didn’t see back then, is why the One appears as many.

Michael Sudduth

(January 16, 2013; revised January 24, 2014)

For a discussion on the evolution of my spiritual practice 2013 to present, see my interview with Helen De Cruz (May 2015).

Follow

Follow