I’m a philosopher by profession, but only because I’m one first by nature. More importantly, the particular kind of philosopher I am at present is a reflection of my total life situation and total life history. It has always been this way. For much of my adult life philosophy was solely a matter of conceptual analysis and logical argumentation, served with a side dish of historical information. Those who have followed my career in philosophy have noticed that philosophy has widened a lot for me in the past five years, partly as a result of my engagement with psychology, partly as a consequence of my embracing eastern spirituality, and partly from being in personal relationships that have profoundly showed me, in the words of Carl Jung, that “the judgment of the intellect is only part of the truth.” My “Cup of Nirvana” blog is an illustration of this widening conception of philosophical inquiry.

I’m a philosopher by profession, but only because I’m one first by nature. More importantly, the particular kind of philosopher I am at present is a reflection of my total life situation and total life history. It has always been this way. For much of my adult life philosophy was solely a matter of conceptual analysis and logical argumentation, served with a side dish of historical information. Those who have followed my career in philosophy have noticed that philosophy has widened a lot for me in the past five years, partly as a result of my engagement with psychology, partly as a consequence of my embracing eastern spirituality, and partly from being in personal relationships that have profoundly showed me, in the words of Carl Jung, that “the judgment of the intellect is only part of the truth.” My “Cup of Nirvana” blog is an illustration of this widening conception of philosophical inquiry.

For much of my career, analytic philosophy, the particular form of philosophy I embraced early in my philosophical education, was a tool to prove that I was correct about something and that someone else was mistaken in a view that contradicted my own. This activity masqueraded in the guise of wanting to know the truth “for its own sake,” but this was simply a clever form of self-deception or – more aptly – bullshitting myself. I now see that I wanted to know the truth because life would be unmanageable if I didn’t know the truth, and a certain disaster if it turned out that I was mistaken. For me, the affect associated with unanswered questions was the same as answers incorrectly answered.

The whole force of the compulsive drive for clarity and reasoning was the expression of a deep unacknowledged psychological need to control my world, a need rooted in a childhood destabilized by trauma. Intelligence gave it form as philosophical inquiry, a particular mode of philosophical inquiry. This need emerged, not because philosophy was seen to be an intrinsically joyful exploration. Philosophy may begin in wonder, but it’s often taken up or ends up under the control of fear. For me, the attraction to philosophical inquiry came under the influence of fear and the need for safety. Safety required finding an identity, specifically one that would allow me to exert a high level of control over my world. Logic and reasoning gave promise to answering this need. While the attachment to logic chopping created something of an identity with resources that helped regulate my life at one level, like many defense mechanisms it’s also caused considerable trouble in other respects, especially in the interpersonal domain. That which is unconsciously motivated by aversion is likely to characterize our conscious lives as depression, anxiety, and addictive behavior.

This need for identity and security, appearing as the seeker of clarity and agent of reasoning, has taken different forms, from embracing religious traditions that advertise some kind of “certainty” to enlisting philosophy to defend such religious traditions from attack, to “steam rolling” people with logic when I felt attacked. Psychologically this remains one of the greatest challenges for me, but for sometime now it has been made conscious. Having been made conscious, needs and motivations don’t necessarily dissolve, but the prior relationship to them is changed in their coming into realization. It begins the process of dissolving the otherwise neurotic engagement with the world.

Conceptual analysis and logical argument remain an important feature of how I do philosophy, but the interests and motivations have shifted since seeing through what I’ve been doing most of my adult life. The urge to know because not knowing is scary remains a voice, but it’s now seen to be that and as such it’s only one voice in the choir called “self.” In this seeing, a new love of the process of inquiry and reflection is born, not as a means by which to control the world but simply as part of the process of inner exploration. And there can be joy in the process, regardless of the outcome, because it’s seen that ignorance is OK. It’s OK even if we learn nothing from it. It’s OK just as it is, with no interest in doing anything with it.

From this position, I’m a hell of a lot more likely to have an attitude of acceptance towards people who differ in their opinions from my own. If I’m OK about being mistaken, it’s OK that others are mistaken. I’m simply not going to feel threatened by opinions that contradict my own. For most of my life I was not OK with others being mistaken because I wasn’t OK about being mistaken myself. The attitude towards others was a direct reflection of myself.

I suppose for some people this attitude might move them completely out of the business of philosophical inquiry, or specifically the business of logic chopping and conceptual analysis. Or for some people maybe they lose all conviction of truth if they have this attitude. That’s not the case for me. I can have conviction that a certain statement is true or false or that an argument is poorly constructed or nicely constructed. I can evaluate opinions and arguments, and I certainly haven’t lost the interest in doing so. Yes, I can even feel strongly that an opinion or argument is bullshit. The crucial thing is having the disposition to feel no different in this moment if I came to see I was the one who was endorsing bullshit. There’s a growing part of me that actually welcomes the realization that I’m full of shit or that I’ve made some huge mistake in an argument. In a sense, I’m a bullshit philosopher, but so are others, as I find it hard to believe that I’m someone special here, an exception to the rule. But is it OK to be a bullshit philosopher? This would seem to be the real question. For me, it is. Bullshit and truth are equally OK. Or, to be more precise, life is no less OK when bullshit is present than when truth is present. What makes bullshit and truth equally OK is to see that they are each part of life as it is happening, and I’m not something separable from life as it is happening.

Am I not without conviction for all of this though. For me, the problem has never been the strong conviction that I was correct. It was the force behind this conviction. What about having confident assertion, not because I can’t afford being mistaken, but because – from the perspective of my ultimate intention for living – I don’t give a shit if it turns out that I’m mistaken. Even in the telling of this, there is just a story being told. Fundamentally, no one knows most of the shit they claim to know. But we play the “knowing game.” Now I don’t tell myself “stop playing the game.” This would just be another form of aversion. No: this is what my mind does, and I understand it has a need to play this game. It wants to treat life as a perpetual drama whose essence can be captured by tidy definitions, numbered propositions, and the rest of the paraphernalia of formal logic. Maybe some truth enters into this drama, of course. For me, though, the thing is to see it as a game. This introduces a certain playfulness that breaks the edge of the neurotic personality that loves to take this business, like everything else, more seriously than it actually is.

I aim to make rigorous arguments, and I love conceptual analysis and logic chopping. You’re not about to find me soft-pedaling my critical engagement of survival arguments. Why not, if it doesn’t ultimately matter? Well, it matters and it doesn’t matter.

It matters in the sense that in the doing of it there’s an important part of me that is acknowledged and seen. There’s a security that I give to a part of myself, and this is important. The need that is met in this process comes from hitherto unconscious parts of the self being seen in the conscious life of the self. Others cannot give this, but this is what I was previously seeking. So there’s an interesting transition from philosophical inquiry as a way to be seen and validated by others (because of what it produces) to philosophical inquiry as a way of seeing and validating oneself in the activity itself (regardless of what it produces or where it goes). In the latter, “being seen” dissolves in the joy of seeing. Philosophy has become spiritual and therapeutic, but only because it’s reflecting a transformation already in progress.

In other sense, it doesn’t matter. What I am, even in my individual person, is much larger than this part that gets security from dropping into logical analysis, and loving engagement with these parts is just as essential. Neurotic behavior is just compensation arising from psychological one-sidedness. So at some point, the analyzer steps back and just watches the rock guitarist step forward and do his thing. And then there’s the poet writing poetry. There is also the lover connecting with women and the feminine. There is the child playing mini-golf and pinball machines. There is the comedian cracking jokes, generating laughter in some and irritation in others. Here is the choir I call “self.” Let them sing, and let them sing together. Singing and dancing is what really matters, for this has the power to reveal our deeper nature and its connection to the transcendent, which is why Rumi called it a path to God.

Carl Jung once noted that philosophy taught him that all psychological theories, including his own, were a subjective confession. I suspect that philosophy too, the form it takes and how it’s implemented, is fundamentally a subjective confession. At any rate, it has been for me. Even when I’m dealing with conceptual analysis and formulating precise arguments, I am necessarily encountering and speaking about myself. Perhaps this is the most important truth to be realized, the truth about one’s personal story. To get there requires penetrating everything we have erected to keep us from ourselves.

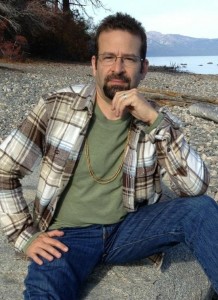

Michael Sudduth

Follow

Follow