I’ve spent most of the past twenty years playing conceptual chess and solving logical puzzles, an essential part of my work as a professional philosopher. Like finding your way out of a labyrinth, that can be fun, especially if you don’t take it too seriously. But other modes of discourse, exploration, and expression have also played a prominent role in my life, mainly music, poetry, and story telling. And in my most challenging hours, I’ve always turned to music and creative writing, not analysis and logic chopping.

During the past decade I have on different occasions happily digressed from scholarly projects to explore fiction writing, something I first broached with the writing of zombie stories in my teenage years. And in the past three years, I’ve regularly supplemented my scholarly writing with contemplative writing and poetry, some of which I’ve published in my blog. In the past eleven months, though, I’ve returned to fiction writing. It’s been a very sustained and concentrated effort, inspired largely by Stephen King. Here I offer some reflections on my movement into fiction, King’s role in it, and what I’ve found beneficial about this new direction in my writing.

My Return to Fiction Writing

Some very unusual experiences while living in an 1817 home in Windsor, Connecticut inspired my first attempt at writing a novel. That was back in 2008. The storyline of the novel emerged from two situations that kept popping up in my head. The first was a very ordinary one: what if a young widow bought an old house and started restoring it, as a way of working through grief after the death of her husband. The second situation was a paranormal one: what if place can absorb and retain the memories and emotions of people who reside there? These two situations gave birth to an interesting story that linked a young woman’s pursuit of psychological healing, a retired philosophy professor’s newfound life as gardener, and the Connecticut witch trials.

I never finished the novel, but the hundred pages I wrote represented my first serious exploration of fiction writing since my teenage years. Back then I wrote zombie stories. That was a great way of throwing some water on the flames of teenage angst. It was also a nice way to exact a little poetic justice on the asshole jocks in junior high and the stuck-up cheerleaders who didn’t give me the time of day. My friends and I had a good laugh, and—perhaps most importantly—no one got hurt.

My early exploration of fiction writing was also something of a tribute to George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. I must have watched that film with friends over hundred times by the time I graduated from high school. We had the entire script memorized. That movie was simply the shit.

In high school my creative expressions shifted to music. After starting a heavy metal band in the 1980s, the writing of zombie stories gave way to lyric writing. The zombies were still alive, but they walked in a larger supernatural field with vampires, ghosts, and demons.

In the past year, I’ve returned to fiction writing. I have two novels and a novella underway. Each story explores dissociative psychology. One is a straight psychological thriller; two involve ostensible paranormal phenomena and explore the ambiguity between such phenomena and abnormal psychology. I’ve nearly completed one of them—Shadow at the Door. I’ll have more to say about this in a future blog once the novel is complete.

Inspiration from Stephen King

Why have I returned to fiction writing?

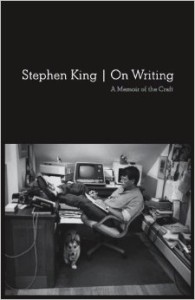

Late last year I happened upon Stephen King’s On Writing (2000) while perusing books at a Barnes and Noble bookstore, appropriately the same venue where eight months later I’d participate in a Q&A with King himself. A protracted moment of lucid disgust with academic philosophy led me to wander aimlessly through the store. I eventually wandered into the fiction section, and there I saw Stephen King’s On Writing. “Oh yeah, King,” I thought. A series of images lit up my mind—Jack Nicholson slashing through a bathroom door with an ax (Here’s Johnny!), Kathy Bates hobbling James Caan’s cockadoodie legs, and Sissy Spacek using psychokinetic powers to seriously fuck up her cruel high school peers.

I picked up the book and began reading it. Within minutes it melted away my disgust with academic philosophy. In fact, it melted away academic philosophy altogether. What a rush!

It only took five pages to persuade me to buy the book, which was so enthralling that I completed reading it in two sittings. On Writing is a brilliant and inspirational memoir-style exploration of fiction writing, though I think there’s something in it for any writer. And from On Writing I went on to read King stories for the first time—Salem’s Lot, the Shining, Misery, Bag of Bones, A Good Marriage, and a dozen King short stories.

One of the strengths of King’s writing is his ability to reveal that ordinary life is thin and fragile, like the sheet of ice that covers a lake in thawing season. It doesn’t take much for the ice to break and for us to fall through. The abyss is not far away, and our deeper fears are actually very close to the surface of ordinary life. King’s stories allow us to confront these fears but also to develop a certain liberating relationship with them. I think there’s a certain playfulness there that helps us feel more confortable in our skin, darkness and all.

A precondition of this playfulness is an unobstructed transparency about the human condition, and this is a signature of King’s writings. He holds back nothing, and he represses nothing. This allows light and darkness to each break out. And there’s no apology for letting the dark express itself, even if the darker side of human nature wins on occasion. “Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too,” King has said. “They live inside us, and sometimes, they win.”

One must already be okay with the darker side to be fully transparent about it. We hide what we cannot tolerate about ourselves, and that tends to be what we condemn in others. Shame and guilt are the gatekeepers of unsettling truths. Those gatekeepers are rather stingy when it comes to divulging our deeper secrets, even to our selves.

But therein is the magic of King. He busts it all open. He drops you into the abyss, but there’s something redemptive about it. King once said, “Good writing—good stories—are the imagination’s firing pin, and the purpose of the imagination, I believe, is to offer us solace and shelter from situations and life-passages which would otherwise prove unendurable” (Nightmares and Dreamscapes, 6).

The point can be expressed in more positive terms. We might say, with a dash or two of metaphor, that writing opens space large enough to allow our laughter and our tears to be and to dance together. In that dance we don’t merely disclose life’s larger movement. We actually unite with it. That’s redemptive, but it’s not an escape from the dark. It’s a reconciliation to it. It’s Zen on a magic carpet ride.

I’ve always found the dark fascinating and liberating. So it’s no surprise that I should connect with Stephen King stories. This also explains my teenage attraction to the stories of Edgar Allan Poe, and the lyrics of heavy metal bands like Black Sabbath. Of course, it also helps to grow up in the dark—Vietnam, Watergate, the proliferation of serial killers, the rise of horror films, and the threat of nuclear holocaust, if the “big one” didn’t shake, rattle, and roll California into the ocean first. And religion comes in here too. To some extent, I found Christianity appealing in my later teens and early twenties because it acknowledged the more potent devils of our nature.

So King ignites something fairly deep in me. And as a catalyst in my movement towards fiction, he’s really guided a return to something that was very alive for me years ago. Things that were once very alive for us sometimes come back, sometimes many times. They’re not done with us yet. They have something more to say, something more to do, and there’s some new transformation or development awaiting us.

Three Benefits of Fiction Writing

Fiction writing can facilitate personal development and transformation in different ways. Here I’ll just mention three that are particularly significant to me, especially since they stand in sharp contrast to philosophical writing, at least of the sort I’ve practiced for twenty years.

First, fiction writing, like all expressions of creativity, helps loosen the grip of the ego. Fiction invites us to write as unconsciously as possible, just like music invites us to play an instrument or sing as unconsciously as possible. To some degree the process releases the chokehold of the ego, that is, our attachment to a distinct set of interests, expectations, and beliefs—you know, all that thinking that mediates the toxicity of our lives.

By contrast, scholarship and argumentation are very much about a consciously adopted point of view. There I try to make a point, or many if my reader is very unlucky. Even when I’m doing analysis, I’m keeping track of the number and color of the cows behind the fence, how many times they’ve taken a dump, and where the piles of shit are located. The less conscious I am here about what I’m doing, the worse off I am. No scholar likes to step into a pile of shit after all.

Fiction writing moves in the other direction. Throwing oneself far enough into any creative process is similar to the Buddhist experience of “no self.” You can’t be too conscious of what you’re doing while you’re doing it or you’re not going to find any deep satisfaction in it, and you’re also unlikely to do it well. I still remember the three months I worked as an apprentice for a house painting company. Every time I flubbed something on the job, my boss would say to me, “you’re thinking about it too much!” He was right. At any rate, I was too much in thought.

When I’ve been most effective in playing guitar or sports, I wasn’t thinking about what the hell I was doing. And whatever thinking might have been going on, was little more than a ballboy on the sidelines. I wasn’t in it. You have to move from the center, recede into the background so to speak; maybe disappear altogether. That’s the nature of art, whether it’s painting, music, or writing.

The selflessness of the artistic process takes a variety of concrete forms in writing. For example, I have to trust my characters more than myself. I wait for them to say and do things. It’s intuitive writing. In a certain sense, I’m just watching things play out in my mind and writing down what I see happening. The characters, not my conscious intentions, play the deeper role in shaping the development of the story. And it takes a certain amount of cultivated patience to just go with the flow when the characters have something to say or be at rest (take your fingers off the keyboard) when they’ve fallen silent.

When I tell people I’m writing a novel, they want to know what the plot is. I tell them, I don’t have one. That’s truthful, and of course it’s also a good way to get out of talking about your story. Some fiction writers do plot. I’ve done some of this myself, years ago. It’s just not how I do things now. The writing is now more situation-driven, as King often describes it. And the dynamic is entirely different.

Of course, I understand that some people need a meticulous outline of the details of their story worked out in advance, just like some people need to paint by numbers. What’s your plot? Have you identified the antagonist(s) and protagonist(s)? Have you planned the story arc in the right way? Have you avoided head-hopping? All those nagging questions, which, for me, just sound like a good way to distract from story writing. I personally prefer just to write the story, let that flow, get in that zone. There’s plenty of time to address technical questions later and do the needed clean up.

And here’s one of those many points where Stephen King’s observations resonate with me:

I distrust plot for two reasons: first, because our lives are largely plotless, even when you add in all our reasonable precautions and careful planning; and second, because I believe that plotting and the spontaneity of real creation aren’t compatible . . . I want you to understand that my basic belief about making stories is that they pretty much make themselves. (On Writing, 163)

In the writing of my current novel I’ve seen how a story can make itself or be the direct product of what the characters are doing in a very spontaneous manner, without much or any foresight on my part. Over and over, I’ve found myself writing scenes or dialogue that I had no idea I’d be writing until the sentences were being typed. And even where I have some bare bones idea of where things may be going, when the characters clothe it with flesh and blood, there’s still considerable surprise. Nor is the result chaotic or incoherent. What’s amazing is the level of inner coherence that emerges when there’s been no conscious intention to create it. I personally find this more enjoyable than merely filling in the details of an outline.

What is important is that I feel the movement of the story, and that means listening to my characters tell the story. And it’s important not to “push the river.” To the extent that I’m trying to achieve something with the story, I’m not listening to my characters tell the story. And to that extent, I can’t even hear the voice of my characters, much less see them evolve with the story, and that’s all essential to a good a story I think.

Second, there’s a sense in which fiction writing possesses the power to disclose aspects of our inner life, not immediately transparent to us. Someone once asked Albert Camus whether he appears in his own novels as some particular character. He said, no; he’s actually all of them. Arguably, every character is some part of the author (maybe some are a bigger part of us than others), but the salient point is that those parts come into clarity in the process of writing, even if it’s only at the completion of a work or in subsequent reflection on it. And that means there’s quite a bit of self-knowledge delivered in the writing of a story.

Stephen King has often said that while he was writing the Shining, he wasn’t aware that, in writing about Jack Torrance, he was in fact writing about himself. King was the alcoholic struggling for redemption but slowly losing his mind. That hit him later, no doubt in part because the novel became a mirror that enabled him to see his own face more clearly. Hence, King says, “I think you will find that, if you continue to write fiction, every character you create is partly you” (On Writing, 191).

This is not to say that our characters bear no resemblance to persons outside us, but if we look close enough at our most meaningful relationships (the one’s most apt to inspire the creation of our fictional characters), they bear a striking resemblance to aspects of ourselves. The woman you fell in love with it, or the asshole boss you want to punch in the face at least once a week. When you fashion characters after these persons, you’re really writing about yourself.

There’s more to what you call you than what you take yourself to be. The writing process is an activity of this wider field of subjectivity. As such, it’s largely an incursion from the unconscious, not something conscious at all. Fiction opens that door, for writer and reader alike. Whether by sudden fall (through a trap door) or gradual descent (down the basement staircase), fiction takes us to the underworld of our inner life. And a certain change takes place in that journey, for example, the enriching of our perspective and degrees of emotional regulation. In a sense, fiction writing can be a form of therapy, very effective therapy. And perhaps that’s why so many people read fiction.

Third, fiction thrives on ambiguity and open-endedness, and that’s not something characteristic of scholarly writing, the process of argumentation, and criticism. Of course, there’s a place for precision and rigorous reasoning in life, and—contrary to what some of my former Zen teachers have said—criticism too. It’s by no means a bad or counterproductive thing to believe something, to critique, or to reason. Try living without these. That’s just a complete denial of life and the human experience. We can’t escape beliefs, reasoning, and critique, but one can do it with less attachment. And I think that’s what fiction helps cultivate—non-attachment. Perhaps because it sensitizes perspective to its own limitations and thereby opens up further possibilities. And isn’t this true to life? Don’t we live life in the wider space of unknowing, of mystery? We can contently accept our ignorance and learn to play with it, or we can neurotically reject it and live with it dogging us and spinning us out.

This is particularly significant for me since the topics that loom large in my fiction writing are often the same ones I’ve conceptually explored in my philosophical writing. Take the topic of survival of death. I’ve written at length on whether certain paranormal phenomena are evidence for life after death. But if that’s the question I’m asking, I’m working within narrow parameters the question dictates. I’m looking at criteria for evidence, how we assess explanations, and all that. Here I care, for example, whether survival better explains the facts than some rival hypothesis. Was it an actual discarnate spirit or just some psychic imprint left on the environment from some formerly living person? The virtue of an argument might be that it shows one of these explanations is superior, or it might show why it’s difficult to say which, if either, is a better explanation. But this is all about taking up a position of some sort. And it requires being hard nosed and rigorous in reasoning.

By contrast, if I’m writing fiction, I want to leave things as open as possible. I’m dialing-in that aspect of experience. The only positions that matter are those the characters authentically own. And hopefully they don’t agree with each other too often.

Imagine a story in which one character believes a girl is demonically possessed, and another character believes she’s suffering from schizophrenia. As the author, I don’t care which character is correct (hell, maybe they’re both incorrect). I could write that way, but I’m not particularly interested in doing so. I don’t care whether the girl’s really demon possessed, a schizophrenic, or under the influence of pissed off extra-terrestrials. I care about what’s true about the characters, what they believe, and their being true to their own beliefs and acting from their beliefs and intentions.

True, the story might present the skeptic as more reasonable/virtuous than the gullible priest who thinks the girl is possessed. The story might also portray the priest as more reasonable/virtuous than the skeptic. But is that it? I mean, is that the point? Isn’t it rather that the characters are true to themselves? That’s the fertile soil of conflict, and often the path out of it—vital elements of story. And it’s what helps us care about the characters and what happens to them in the story. And maybe, just maybe, this leads the reader into some form of self-realization. After all, the characters of a story are not just a mirror by which the author may see her face more clearly, but it’s also one in which readers may come to see their own face more clearly.

Dreaming with Eyes Wide Open

King has said, “fiction is the truth inside the lie.” Fiction has truth to reveal, but ultimately it’s the truth about the author and reader. And it’s the individual author and individual reader who are the only ones who can know what that truth is. Likewise, the consolation, healing, enjoyment, or satisfaction that a work of fiction brings to life is one the author and reader is uniquely situated to determine for herself. Otherwise put, stories are really, or at least fundamentally, about persons. The persons appear in the pages of the book, and they appear as the eyes behind the book.

As I said at the outset, I’ve spent most of the past twenty years playing conceptual chess and solving logical puzzles. And I’ll probably always do that sort of thing. But I’ve learned that it’s also important to spend a significant amount of time dreaming with my eyes wide open. That’s how King describes the path of fiction, and that seems exactly right.

Michael Sudduth

REVISED 11/29/16

Follow

Follow