In November 2021 the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies awarded Bruce Leininger $20,000 for his essay “Consciousness Survives Physical Death: ‘Definitive Proof’ of Reincarnation.” In his essay, Mr. Leininger presents a chronology of behaviors and claims he attributes to his son James. The chronology spans a seven-year period beginning in 2000 shortly before James turned two years old. Mr. Leininger says his son’s behaviors and claims during this period of time match the life of World War II fighter pilot James M. Huston., Jr. who died in combat on March 3, 1945. Mr. Leininger regards these matches as otherwise inexplicable. For Mr. Leininger, this is proof that his son is the reincarnation of Huston.

In November 2021 the Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies awarded Bruce Leininger $20,000 for his essay “Consciousness Survives Physical Death: ‘Definitive Proof’ of Reincarnation.” In his essay, Mr. Leininger presents a chronology of behaviors and claims he attributes to his son James. The chronology spans a seven-year period beginning in 2000 shortly before James turned two years old. Mr. Leininger says his son’s behaviors and claims during this period of time match the life of World War II fighter pilot James M. Huston., Jr. who died in combat on March 3, 1945. Mr. Leininger regards these matches as otherwise inexplicable. For Mr. Leininger, this is proof that his son is the reincarnation of Huston.

This isn’t the first we’ve heard of the James Leininger story. It first came to national attention in 2004 when ABC Primetime covered the story with Chris Cuomo as the correspondent. Other US news outlets subsequently featured the story. Then in 2009 Bruce and Andrea Leininger published Soul Survivor, co-written with Ken Gross. The book chronicles the events that eventually convinced the Leiningers that their son lived a previous life as Huston.

Reincarnation researcher Jim Tucker investigated the case in 2010 and subsequently published favorable evaluations, including “The Case of James Leininger: An American Case of the Reincarnation Type” (2016). Past-life therapist Carol Bowman, who counseled the Leiningers in 2001 and wrote the foreword to their book, has also written and lectured on the case – for example in “Children’s Past Life Memories and Healing” (2010, pp. 54-58). Bowman says, “the James Leininger case is the best American case of a child’s past life memory among the thousands I’ve encountered” (“Foreward,” Soul Survivor, p. x). A favorable analysis of the case also appeared in journalist Leslie Kean’s book Surviving Death (2017). And most recently, the 2021 Netflix series Surviving Death, loosely based on Kean’s book, featured a segment on the Leiningers.

The Latest Version of the Leininger Story

In “Consciousness Survives Physical Death” (hereafter, CSD), Bruce Leininger presents the latest iteration of the reincarnation story he’s been perpetuating for nearly two decades.

As in his earlier presentations, he focuses on two sets of alleged facts. (i) There are claims and behaviors he attributes to his son James at various points in a seven-year chronology. (ii) There’s documentation allegedly showing that these claims and behaviors match the life and death of Huston. Leininger also claims that the kinds of facts identified in (i) and (ii) have no ordinary explanation – for example, coincidence or ordinary sources of information which might have influenced his son. Mr. Leininger claims that these considerations provide definitive proof of reincarnation. He calls it a proof so “iron clad” that it carries the force a geometric demonstration.

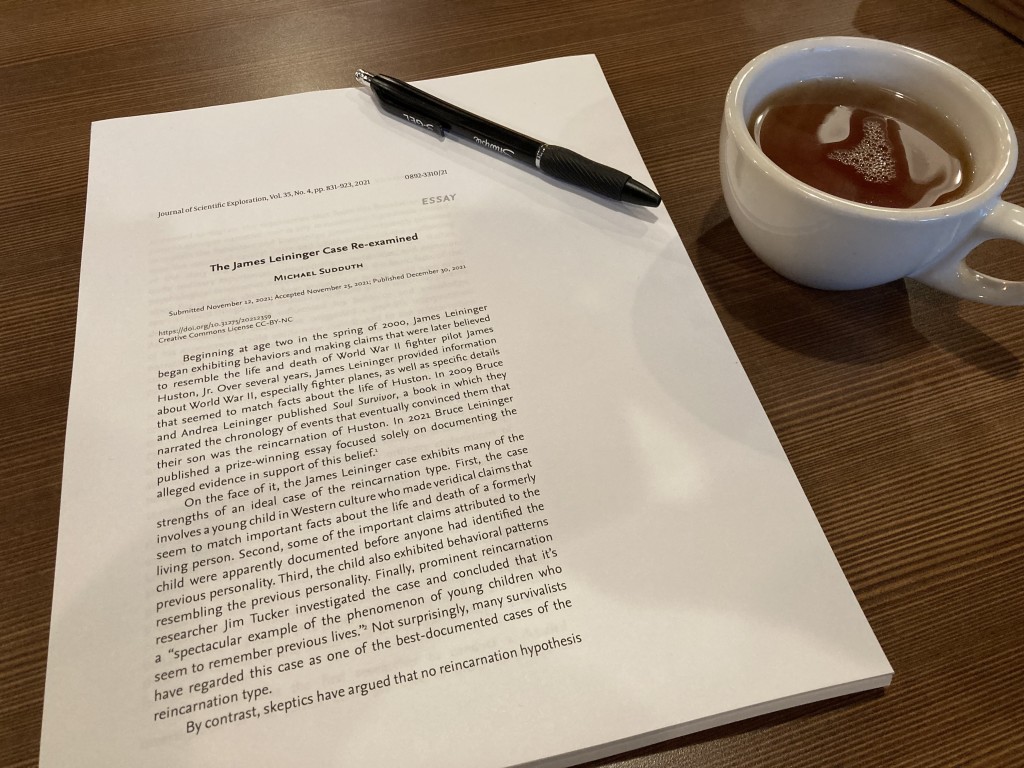

I have previously published “The James Leininger Case Re-examined” (Journal of Scientific Exploration, 35: 4, December 2021). My JSE article provided an extensive critical discussion of this case in connection with Jim Tucker’s investigation and analysis. However, because of the timing of the publication of Leininger’s CSD paper, I was not able to provide any substantial comments on it in my JSE paper. What follows below is a supplement to my JSE paper. It’s not intended to be a comprehensive, line-by-line exegesis and critique of Leininger’s CSD paper. My goal is to illustrate from his paper the problems I discussed in my JSE paper, but with particular attention to the kind of argument Mr. Leininger claims to be offering as proof of reincarnation.

In what follows below, I have in places included links to written and photographic documentation to support my claims. In a couple of places, I embed video clips. It’s not necessary to read my JSE paper before reading this supplement, but some readers may wish to read the more extensive JSE paper first. Although there’s cross-over in content between the two, they have different though complementary objectives.

One final preliminary. BICS published Bruce Leininger’s paper without the supporting documentation Mr. Leininger allegedly included as appendices. At present (1/17/2022), BICS has not published a corrected version of Mr. Leininger’s paper. His narrative remains without any supporting documentation. One of these important pieces of primary-source documentation is the Natoma Bay Aircraft Action Report. Since I acquired a copy of that document during my research, I have uploaded it to my website and link to it below.

Extravagant Claims

The first thing that stands out in Bruce Leininger’s essay is the extravagant nature of his main claim.

In this essay I will present ironclad proof that consciousness survives physical death via this demonstration. This body of evidence or proof was discovered over a seven-year investigation as I worked to validate statements made by my son James. (CSD, p. 3)

This essay will demonstrate an immutable proof, like a proof of Geometry, that reincarnation is a real event in the journey of the soul through eternity. (CSD, p. 5)

I have clearly and unequivocally proved reincarnation is a real event in the survival of the human consciousness after death and proof that the soul is on an eternal journey. (CSD, p. 22)

Bruce Leininger doesn’t say, as other researchers have, that reincarnation provides the best explanation of the facts. He doesn’t say his case presents good evidence for reincarnation. Mr. Leininger says he’s going to present a proof. And not just any proof. Presumably proof is even too weak of a notion to do justice to the evidential force of the facts Mr. Leininger has managed to discover. He’s going to present an ironclad and immutable proof. He’s going to provide a demonstration as logically compelling as a geometric proof. And he will not only prove postmortem survival, but the existence of a soul that will exist for eternity.

These claims are excessive and border on the absurd and outrageous. Even a modest familiarity with the literature on life after death over the last century shows how far Bruce Leininger’s thinking has strayed from the beaten path. No serious thinker in the survival debate believes we can prove there’s life after death, much less with the force of geometric demonstration. And proof of the persistence of consciousness after death would not prove the existence of a soul, much less immortality.

Stephen Braude, in his prize-winning essay in the Bigelow competition, nicely brings attention to the importance of evidential modesty.

In order to evaluate the cases taken as evidence of postmortem survival, we must first be clear about what, exactly, we’re considering or hoping to establish. Strictly speaking, we have no proof of survival. Nor can we. We know quite well what proof amounts to in formal systems such as logic and mathematics. But empirical claims never enjoy that degree of certitude, and yet we can still have good reasons for believing many things that nevertheless remain vulnerable to possible revision or subsequent rejection. So what participants in the survival debate need to consider is something more modest than a slam-dunk proof—namely, whether there’s sufficient evidence for, and a rational basis for belief in, the survival of bodily death. (Braude, “A Rational Guide to the Best Evidence for Survival,” p. 1, 2021)

Mr. Leininger is not adequately familiar with the literature on survival to understand what the crucial issues are. Nor does he understand how participants in the survival debate have framed their arguments over the past century. He also doesn’t understand what a proof demands, or he has greatly exaggerated the evidential force of the presumed facts, and his own logical prowess. Curiously, Leininger cites Jim Tucker as a prominent researcher who has vouched for the case (CSD, p. 7), but even Tucker doesn’t make such extravagant claims.

But Mr. Leininger’s understanding is otherwise flawed. Shortly after making the above claims, he says: “The preponderance of evidence allows for no conclusion other than reincarnation” (CSD, p. 7). Preponderance of evidence and proofs (geometric or otherwise) are very different kinds of inferences. The latter involves a necessary inference: if the premises are true, then it’s impossible for the conclusion to be false. The former involves a probabilistic inference: if the premises are true, then it’s improbable that the conclusion is false.

Preponderance of the evidence is a legal standard. In strict logical terms (minus legal caveats) it means given evidence e, some statement h has a probability greater than .50 (or 1/2). In other words, given the evidence e, h is more probable than not. Therefore, any claim established by the preponderance of the evidence is logically consistent with and thus allows other conclusions, including not-h. (And that’s true even when various legal caveats are added.) This is also true for clear and convincing evidence and proof beyond a reasonable doubt. These are also probabilistic inferences, though stronger than preponderance of the evidence.

Mr. Leininger is clearly confused about the concepts he’s recklessly brandishing.

Extracting an Argument

Another problem is that Leininger nowhere presents an actual argument for his son being the reincarnation of James Huston, Jr. I don’t mean that he doesn’t provide a logical demonstration – clearly, he doesn’t do that. I mean he presents no clear argument at all. A chronology is not an argument. A narrative is not an argument. A list of facts is not an argument. Assertions about evidence is not an argument. Then again, the failure to present a clear argument is a common problem in the literature on survival. Perhaps we shouldn’t dwell on this particular flaw.

In the interest of charity, let’s consider what Mr. Leininger does give us in the paper. We can work from there and try to ferret out a suggested argument.

- Mr. Leininger provides a detailed chronology in which he lists things James allegedly said and did.

- His “chronological trail” also includes references to sources that provide alleged confirmations. For example, he references sources that document that the Leiningers had on earlier occasions attributed to James some of the same claims and behaviors Mr. Leininger attributes to him in CSD.

- More importantly, Mr. Leininger references primary source documents about Huston. These supposedly show that what James said or did is am exact match to facts about Huston, especially the manner and circumstances of Huston’s death. For example, he says, “All of James Leininger’s (James) words and actions regarding his past life were accurate depictions of his prior incarnation” (CSD, p. 6), and “The facts never varied from or differed with anything he said about his past life” (CSD, p. 7).

- Concerning the information James conveyed and his behaviors, they either “seemed impossible” for a child (CSD, p. 8) or “there is no way he could have known that detail unless he had been there” (CSD, p. 14). He also claims that the matches are not inexplicable by coincidence (CSD, p. 20).

Mr. Leininger’s explicit claims at least suggest an argument.

What then is the suggested argument? Something like this:

(P1) James made the claims attributed to him in the chronology and made them at the times specified in the chronology.

(P2) James exhibited the behaviors attributed to him in the chronology and exhibited them at the times specified in the chronology.

(P3) All the claims and behaviors attributed to James in (P1) and (P2) exactly match James Huston, Jr.

(P4) It is impossible that the matches in (P3) are mere coincidences or that James acquired the information from ordinary sources.

So:

(C) James Leininger is the reincarnation of James Huston, Jr.

To reiterate, this represents my standardizing of what seems to be Mr. Leininger’s argument. He only suggests this argument. I’m simply trying to clarify the kind of reasoning he seems to be groping after based on his explicit claims.

Defects in the Suggested Argument

Bruce Leininger’s argument is not a valid deductive argument. The premises don’t logically entail the conclusion. It’s possible for each of the premises to be true and the conclusion false. So, the argument isn’t a logical demonstration. Also, the premises, even if true, don’t have the degree of warrant that characterizes premises in a geometric demonstration. Mr. Leininger’s argument isn’t a proof of anything, much less an ironclad, immutable, and definitive one.

Of course, we could whip the argument into a more respectable or at least less implausible form. For example, we could change the impossibility of coincidence and ordinary sources in (P4) to the improbability of coincidence and ordinary sources. And we could qualify the inference to the conclusion as a probable inference – for example, as being more probable than not. I don’t think this would make the inference a good one, but at least it wouldn’t be transparently implausible.

Regardless of whether we take the argument in the strong or more modest form, the premises are the main problem. There are compelling reasons to think the premises are false or at least that Leininger has failed to show that they are true. This is important. Whatever the exact structure of the argument he’s suggesting, it clearly includes the above claims or something close to them. So, regardless of the exact form or structure of his argument, his reasoning is flawed because it depends on unwarranted claims.

In my JSE paper I present a variety of considerations that bear on the rationality acceptability of (P1), (P2), (P3), and (P4). I argue that these claims are either false or we have insufficient reason to think they’re true. They are, therefore, unwarranted claims. And if we’re not warranted in accepting these claims, we’re not warranted in accepting the conclusion based on them. Hence, Mr. Leininger fails to offer a good argument for the claim that his son is the reincarnation of James Huston, Jr.

Let’s take a careful look at (P1), (P2), (P3), and (P4).

Premises (P1) and (P2) – The Chronology of Events

The rational acceptability of premises (P1) and (P2) depends on there being a credible chronology of events, but Bruce Leininger’s chronology of events isn’t credible. Consistency is a necessary condition for credibility, especially with respect to structural features of a narrative or claims essential to the content of the narrative. Between 2002 and 2021, Bruce Leininger has offered multiple chronologies. CSD is the latest version of an old story. These chronologies are not merely different; they are structurally and substantively inconsistent with each other. For example, they involve inconsistencies with respect to what James said and when he said it. These inconsistencies also appear to be part of a wider process of narrative redaction based on what the Leininger’s subsequently learned about Huston’s life.

My JSE paper provides a thorough examination of narrative inconsistencies prior to the publication of Leininger’s CSD. Regrettably for Leininger, CSD introduces even more inconsistencies and engages in more suspicious chronological redaction.

One glaring example of a new inconsistency concerns item (4) in Leininger’s CSD chronology.

He writes:

4) July – August [2000] – By this time James also said he flew a Corsair

He indicated several times the Corsair wanted to turn or flip to the left when it took off and the tires broke a lot when the plane landed. (CSD: 9, emphasis mine)

According to item (4), James communicated the specified details about the Corsair (in italics) in July or August 2000. But according to Soul Survivor, James didn’t offer these specific details concerning the Corsair until May 2002.

Describing the circumstances of the filming of the 2002 ABC program in May 2002, the Leiningers state the following in Soul Survivor:

[Shalini Sharma] asked him [James] to show her a picture of a Corsair. So he got out one of Bruce’s books and picked out the Corsair. “That’s a Corsair,” he said. “They used to get flat fires all the time! And they always wanted to turn to the left when they took off!” He had never said that before – never given the characteristics of the plane. (SS, p. 124, UK edition)

In CSD Leininger describes the above incident about item (18).

18) 1 May 2002 – Shalani Sharma 20/20 TV comes to interview us for a TV show being planned. She bought James a toy Corsair and while talking to Shalini about the plane James told her that he remembered Corsairs getting flat tires and always wanted to turn to the left when taking off. (CSD, p. 12)

Item (4) indicates James made the specific Corsair claims in summer 2000. Item (18) says he made them on May 1, 2002. However, notice what Mr. Leininger doesn’t say under (18). Unlike the account in Soul Survivor, he doesn’t say that the May 1, 2002 incident was the first time James made the specific claims about the Corsair. Given what Mr. Leininger says under item (4), that obviously can’t be the case. The narrative in CSD implies James first made these claims in summer 2000, then repeated them on May 1, 2002. If the chronology in Soul Survivor is correct, Bruce’s chronology in CSD is incorrect. If the chronology in CSD is correct, then the chronology in Soul Survivor is incorrect.

The chronological discrepancy is off by nearly two years. The discrepancy is a straightforward logical inconsistency; the accounts in SS and CSD can’t both be correct. Nor is the inconsistency innocuous. It bears on the plausibility of ordinary sources of information which might’ve influenced James. Between summer 2000 and spring 2002, James acquired information about aviation and WW2 planes from a variety of ordinary sources. By relocating these specific Corsair claims under July-August 2000, Mr. Leininger simultaneously inflates the content of what James said early in the case and limits what James could’ve been exposed to that would’ve supplied the information in a quite pedestrian manner.

Other new changes to the chronology introduced in CSD mask earlier inconsistencies.

For example, in Soul Survivor the Leiningers indicate that past-life therapist Carol Bowman got involved in the case in winter 2001, more precisely February 2001 (SS, pp. 116-117). However, in other chronologies – for example, the 2020 documentary the Great Beyond Revealed – Bruce Leininger has indicated that Bowman got involved in summer 2000, perhaps as early as July 2000. Curiously, in CSD Mr. Leininger makes no mention at all of past-life therapist Carol Bowman, though he mentions Jim Tucker. It’s as if Bowman never had anything to do with this case. This is a peculiar omission. I’ll show its evidential significance below, but it’s otherwise a striking alteration to the story given Bowman’s prominence in Soul Survivor. After all, she had a role in the story at two crucial points in its evolution, and she wrote the foreword to their book.

Other features of the CSD chronology repeat later alterations to the story.

Consider item (8).

8) 24 November 2000 – Day after Thanksgiving – IWO JIMA

While waiting for cartoons to start I was looking over a book “Battle for Iwo Jima” by Derrick Wright. I had ordered it to give to my father, a WWII veteran Marine, James was sitting on my lap looking at photos with me. Pointing to a photo of Iwo Jima he said “Daddy, that is when my plane got shot down.” Upon examining the report I found 27 August I verified the ship supported the battle of Iwo Jima... John DeWitt, the ship historian also informed me that only one man from VC-81 was killed during the Battle for Iwo Jima – James McCready Huston, Jr. (CSD, pp. 10, 13)

Although this account matches the claim the Leiningers attribute to James in Soul Survivor (SS, p. 104), compare it to Bruce Leininger’s version of the story in the 2004 ABC Primetime episode:

Chris Cuomo [narration]: “And one day while leafing through a new book about the Battle of Iwo Jima, Bruce turned to an aerial photo of the Pacific island. James was seated nearby.”

Bruce Leininger: “He pointed to it and goes, ‘Daddy, that’s where my plane was shot down.’ And I said, what? And he said, ‘My airplane got shot down there, Daddy.’ And I just went… I just went blank. I couldn’t say anything.” (Video: Unexplained Phenomena, 0:08:26-0:08:50).

This was no mere slip-up on Bruce Leininger’s part. He said the same thing in a 2002 unaired ABC program on the James Leininger story. He also said it in 2005 news segments. And in an unpublished 2003 chronology of events, Mr. Leininger attributes to his son the claim that his plane was shot down at Iwo Jima. Prior to the Leiningers’ book, the claim they attributed to James was unambiguously a claim about the location of the plane crash. However, beginning with their book, the claim is not an unambiguous claim about location. It’s an unclear claim Mr. Leininger interprets as James saying that his plane was shot down during the battle of Iwo Jima. Nor is this change innocuous. For reasons to be explained below, the change is evidentially significant.

Premise (P3) – The Alleged Matches to James Huston Jr.

As for (P3), we have overwhelming reason to think it’s false.

Recall that Mr. Leininger makes some very strong claims about the extent to which James’s claims matched Huston.

The evidence presented describes who he was [as Huston], how he was killed, where he was killed, when he was killed and also numerous details of his past life family and intimate details of numerous other events and other people James encountered and knew as Jimmy.

The facts never varied from or differed with anything he said about his past life. The result – the best documented case of reincarnation as claimed by professionals studying reincarnation. (CSD, p. 7).

What are we to make of this?

The Iwo Jima Attribution

Many of the “accurate” claims Mr. Leininger attributes to James in his BICS paper are later redactions of what James allegedly said. These redactions occurred only after the Leiningers had learned facts about Huston and his death.

A stunning example of this is item (8), James’s alleged Iwo Jima claim discussed above. James pointed to an aerial image of the island of Iwo Jima and said his plane crashed there. He gave the location of his plane crash as Iwo Jima. Beginning with Soul Survivor, Mr. Leininger changed the claim he attributed to his son to “That’s when my plane crashed.” This change came after Bruce Leininger learned that Huston’s plane was shot down at Chichi Jima, a different island about 200 miles north of Iwo Jima. So the original claim is false. But Huston’s death did occur while the Natoma Bay – the carrier on which Huston was stationed and flew from the day of his death – was supporting operations at Iwo Jima. On account of its vagueness, the claim later attributed to James has the advantage of not being obviously false.

Jim Tucker asked Bruce Leininger about this discrepancy. Mr. Leininger allegedly said he later correctly recalled that James had said when not where (Tucker, Return to Life, p. 75). So, this means Mr. Leininger incorrectly remembered this event for nearly a decade. Mr. Leininger acknowledges how important this anecdote is (SS, p. 104; cf. CSD, p. 10). Getting this fact wrong undercuts Mr. Leininger’s reliability as a witness. But also, we have no more reason to suppose that when – if that’s what James actually said – was intended as a temporal reference than a location reference for which James had used the wrong word. This is hardly a surprising error for a two year old to make. Yet, Mr. Leininger would have us believe that his son’s claim is nonetheless veridical.

Mr. Leininger commits a common fallacy. He changes the narrative so that it better aligns with subsequently discovered facts. In Soul Survivor Mr. Leininger says that he initially discounted Huston as the pilot in his son’s narrative because the facts he discovered between September and December 2002 didn’t fit James’s claims. For example, Bruce reasoned, “Huston wasn’t even killed at Iwo Jima. He was killed on a mission a couple of hundred miles away, at a place called Chichi-Jima” (SS, p. 141). Clearly, Mr. Leininger was sure his son had given the location of the plane crash. Since the facts didn’t match, he was reluctant to accept Huston as the previous personality. But change what James said and the discrepancy goes away. Problem is, there’s no independent reason to suppose that James intended to give the time period of his crash. Claiming otherwise looks suspiciously like painting the target around the spot where the dart has landed and shouting bullseye.

The Description of Huston’s Death

Bruce Leininger’s description of the content of James’s nightmares and the related claims he attributes to him are far from being an exact match to the circumstances of Huston’s death. It’s only a logical sleight of hand that generates an impression to the contrary.

He says the following in CSD:

My son, James Leininger, was born in San Mateo, CA. Shortly after his second birthday 10 April of 2000 he began to have violent nightmares or night terrors 4-5 times per week and this went on for several months.

“Airplane crash, on fire… little man can’t get out” were the first discernible shrieks from my son, as he thrashed about under his covers. It seemed as though he was trapped fighting for his life. It turns out – HE WAS – reliving his death, 3 March 1945.

A single-engine fighter flown by James went up in flames after being hit in the engine and crashed in Futami Ko (harbor). (CSD, p. 6)

2) Mid-April 2000 – Frequent nightmares began occurring 4-5/week

These occurred until August / September 2000 when his memories became spontaneous while fully awake and not as a nightmarish event. His initial discernible comments “Airplane crash in water on fire. Little man can’t get out.” (CSD, p. 9)

13) Date 1 September 2001 – While playing with an airplane in the sunroom, James stood up and saluted saying “I salute you and I’ll never forget. Now here goes my neck.” During the same play period he spontaneously said “Before I was born, I was a pilot and my airplane got shot in the engine and crashed in the water and that’s how I died.” (CSD, p. 12)

So, according to James Leininger, Huston’s plane was shot in the engine, burst into flames, and he was trapped inside the burning plane. The plane then crashed into the water. And that’s how Huston died. This narrative is repeated throughout Soul Survivor.

We’ve already seen how James was incorrect about the location of the crash. But it’s worth noting that Mr. Leininger leaves out a couple of crucial details in CSD. James reportedly said that Huston was still alive before impacting the water and after. Huston was alive and trying to extricate himself from the sinking plane. Andrea Leininger said, “After his plane was hit in the engine, it crashed nose first into the water. From what my little James told me after his nightmares, he was alive in the plane when it went into the water, and was kicking to try and break out the canopy to escape the sinking plane… James Huston drowned in the plane, not as a result of the crash.” (A. Leininger, “Leininger Case on ABC – What Did You Think?” Reincarnation Forum, July 9, 2005). Curiously, Soul Survivor and Mr. Leininger’s CSD paper omit this interesting detail.

But how accurate is little James Leininger’s account of what is supposed to be Huston’s crash on March 3, 1945? Mr. Leininger would have us believe it’s completely accurate. But this is false.

The most detailed description of Huston’s crash in primary source documents is in the Natoma Bay Aircraft Action Report written up proximate to the mission in which Huston was killed. That military document says the following:

All aircraft recovered to the west toward the entrance of the harbor. Heavy anti-aircraft took them under fire from each side of the harbor. It was thought to be 3 inch batteries. Lt (jg) J.M. HUSTON was apparently hit by this fire as he approached the harbor entrance. None of the other pilots saw a hit and his airplane was not on fire, but it suddenly nosed over into a 45 degree glide crashing into the water, exploding and burning. At the time the plane nosed over, it was at about 1500 feet altitude and was estimated to have crashed while making about 175 knots. There was no wreckage left afloat and only a greenish yellow spot on the water marked the crash. There was no evidence of a survivor and it is believed that it would have been impossible to survive the crash and resulting explosion. (Position of crash is indicated on diagram). The position of the crash is in enemy territory but possibilities of compromise of classified material is considered improbable. He may have been hit and killed by light fire as no one reported observing any damage to the plane; most of the bursts in the vicinity where he crashed were from 3 inch (or equivalent) guns. (U.S.S. Natoma Bay Aircraft Action Report, sheet 4, emphasis mine. Full six-page report: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6)

This report is clear about several aspects of Huston’s crash that bear on the narrative Bruce Leininger attributes to his son.

- It indicates that prior to Huston’s FM-2 Wildcat impacting the harbor at Chichi Jima, his plane was not on fire and eyewitnesses didn’t observe any damage to the plane.

- The report also indicates that it was believed to have been impossible for Huston to survive the impact and resulting explosion.

- Moreover, since none of the eyewitnesses observed the plane being hit or damaged, the report conjectures that anti-aircraft fire may’ve penetrated the plane and killed Huston. As a result the plane nosed over and crashed into the harbor.

None of this supports the narrative of Huston being trapped in a burning plane and trying to extricate himself, much less surviving the impact and dying from drowning after a failed attempt to extricate himself from the sinking plane. Quite the contrary; the report refutes this narrative. Although Mr. Leininger references the Aircraft Action Report as supporting documentation in his essay (CSD, p. 23), he doesn’t acknowledge that it disconfirms several of the crucial claims he attributes to James – for example, items (2) and (13), and Mr. Leininger’s preliminary narrative (CSD, p. 6). (For a detailed discussion and analysis of the aircraft action report, see Section 4 of my JSE paper.)

Corsair Attributions

Mr. Leininger’s CSD paper also relies on later reinterpretations of claims attributed to James. These are post hoc reinterpretations since what the Leiningers later learned about Huston informed the interpretation. For example, James’s early claims about flying a Corsair seemed quite naturally to imply that he flew a Corsair off a boat called Natoma and was shot down while flying the Corsair. And that’s how the Leiningers interpreted him for nearly two years, until they learned that neither was true of Huston, but that he did test fly a Corsair about a year before his death. Item (4) in Mr. Leininger’s CSD chronology is a post-hoc reinterpretation of what James said. He also fails even to acknowledge the ambiguity surrounding the claim in question in its original context. (For a detailed discussion of James’s Corsair claims, see Section 5 of my JSE paper.)

It should be clear that premise (P3) – the alleged similarity between James Leininger’s claims and facts about Huston’s life – is false. Mr. Leininger had said, “All of James Leininger’s (James) words and actions regarding his past life were accurate depictions of his prior incarnation” (CSD, p. 6) and “The facts never varied from or differed with anything he said about his past life” (CSD: 7). These claims are not just false. They are false multiple times over.

The falsehoods are egregious, but what’s arguably more egregious is how Mr. Leininger’s crafting of his story conceals the falsehoods. He’s followed a fairly well-known recipe for creating a deceptive appearance of genuine matches between what a child subject says and facts about a formerly living person. Redact claims attributed to the subject after you learn facts about a deceased person. More specifically, change what you say the subject’s claims originally were or change your interpretation of the claims you attributed to the subject. After all, it’s easier to fit a dart into the bullseye when you paint the target around the spot the dart has landed. Do this especially when you discover that claims you originally attributed to a subject are (probably) false. In other words, create alternative facts. Also, expunge from your narrative other claims you once attributed to a subject that are improbable or which are specific enough to open themselves to disconfirmation. Finally, ignore facts that don’t fit what the subject claims. Leininger has used every ingredient in this recipe to fashion a highly misleading narrative.

Premise (P4) – Ordinary Sources of Information

What about (P4)?

I noted two forms of (P4).

(P4) It is impossible that the matches in (P3) are mere coincidences or that James acquired the information from ordinary sources.

and

(P4*) It is improbable that the matches in (P3) are mere coincidences or that James acquired the information from ordinary sources.

Leininger appears committed to (P4), but (P4) is obviously false. I suggested (P4*) as an alternative since it’s not as obviously false as (P4). But, as I’ll show below, (P4*) is also false. Hopefully it’s clear that if the logically weaker claim (P4*) is false, then the logically stronger claim (P4) is false.

Mr. Leininger nowhere provides evidence for (P4) or (P4*). This alone would make this premise unwarranted. You don’t provide a good argument for reincarnation by relying on a premise that’s at least as equally contentious as the conclusion itself. And even if (P4) or (P4*) were less contentious than the conclusion, it’s the kind of claim that needs support. Why should we think it’s true? Leininger never says. He only offers his impression that it seems to him to be true. That’s obviously no reason to think it’s true.

But the more serious problem is that there’s compelling reason to think the contentious premise is false in both of its forms. Mr. Leininger doesn’t as much as acknowledge the counter-evidence, much less does he critically address it. It’s not even on his radar. In my JSE paper, I chided Jim Tucker for mishandling this aspect of the case – he apparently wasn’t aware of several ordinary sources of information to which James was exposed. But it’s more egregious in Mr. Leininger’s case. Unlike Tucker, Leininger had first-hand acquaintance with his son’s day-to-day life as this story unfolded. And he was directly responsible for exposing James to several ordinary sources of information.

The Cavanaugh Flight Museum

Bruce Leininger says the following in CSD:

As an infant/toddler James was a fanatic about anything involving aircraft. By age two he had accumulated several toy aircraft and exhibited an exasperating troubling habit of crashing them into a coffee table knocking off the propellers. If we were in a car or the backyard and he saw an aircraft flying he would excitedly point at it. Because of his interest I took him on a visit to the Kavanaugh [sic] Flight Museum in mid-February 2000 just prior to moving from Dallas, TX to Lafayette, LA. Part of the inducement was the promise of ice cream at a McDonald’s nearby. The visit was exasperating. He was uncontrollable with excitement. A visit that could take less than hour took almost three. He vigorously protested every time I tried to take him the hanger housing the WWII aircraft and would run back toward it every time we left. Once there he stood transfixed on several occasions for 10-15 minutes staring and pointing. It was as if James was hypnotized by the WWII aircraft. (CSD, p. 8)

Mr. Leininger doesn’t say much in CSD about the content of the Cavanaugh Flight Museum. In Soul Survivor he provides a bit more detail – for example, that James saw the FM-2 Wildcat and P-51 Mustang planes on display, and that he took James to the museum again for another lengthy visit on Memorial Day weekend that same year (SS: 23-27). Bruce Leininger and his wife Andrea have repeatedly assured the public that James wasn’t exposed to anything that could be the source of the knowledge he exhibited in the early months of the case – for example, his identifying a drop tank on a toy plane, the imagery of his nightmares, his knowing the name of the Corsair fighter plane, and his ability to identify the Japanese by the “big red sun,” the red dot symbol. They’ve been explicit that none of these specific items can be traced to anything James saw or heard at the Cavanaugh Flight Museum.

Bruce Leininger has said:

He knew the plane [Corsair]. How could James know the name of a World War II fighter aircraft, much less with certainty that it was the aircraft in the dream? And how the hell did James know it launched from aircraft carriers? Nothing that he had ever seen or read or heard could have influenced him to have this memory? (Quoted in Leslie Kean, Surviving Death, p. 21)

In the 2004 ABC Primetime segment, Andrea Leininger said:

I knew what he watched on television. I knew what stories I read to him. I’m a protective, first-time southern mother. There’s no other place he could have been getting this information. (See Video: Unexplained Phenomena, 00:12:17-00:12:27)

She’s also said:

The flight museum has refurbished planes in it from WWI, WWII, plus the Korean War, Vietnam, and then more modern military aircraft. There was no Corsair on exhibit at the time, and there were no videos of burning or crashing planes. Just large hangers with the aircraft from each era sitting out on display. It was about 4 months after the trip to the museum that James had his first nightmare. When the whole night terror thing started, we briefly considered the trip to the museum as a cause, but since he had been just a very young toddler, so much time had passed (four months is a long time in toddler years!) and none of what he was telling us could be traced back to that museum visit, we eliminated it as a possibility. (Andrea Leininger, “Re: Confessions of a Skeptic” in Soul Survivor Blog, Comment 418, September 30, 2009)

The problem with the Leiningers’ testimony at this crucial juncture is that it’s demonstrably false.

With assistance from current and former staff at the Cavanaugh Flight Museum, I was able to reconstruct the content of the Cavanaugh Flight Museum when James visited in 2000. In my JSE paper I document this content in detail. The museum had a variety of Corsair toys and models airplanes in the gift shop where James spent considerable time. It had a large Japanese battle flag featuring the “big red sun” in the hallway of the gift shop. In the gallery connected to the gift shop, there were large images of Corsair planes in combat over islands. There were several drop tanks on display on planes and in an artifacts hangar. And there was a room with aviation videos on WW2 and Vietnam which the public could view. We have here a lot of information Mr. Leininger attributes to James and treats as inexplicable but for the reincarnation hypothesis – for example, items (1), (2), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), and (12). See my Cavanaugh Flight Museum page for images of exhibits and the museum gift shop.

Blue Angels and Corsair Videos

Another curious omission. Bruce Leininger says nothing in CSD about the Blue Angels aviation video James watched. Bruce purchased it for James during their February 2000 visit to the museum (SS, p. 24). James watched the video regularly for over a year, so much so that Bruce had replace it at least twice. Regrettably, Mr. Leininger has repeatedly given the incorrect name of the video. Despite the inability of previous researchers to locate the video, we now know its name. It’s Blue Angels Around the World at the Speed of Sound (A&E 1994). Dennis Quaid narrates, and the video features the Queen song ‘It’s a Kind of Magic.’

How is the Blue Angels video relevant?

The Blue Angels video has a combat strike scene with images of a fighter plane being shot and bursting into flames. The video also illustrates many of the behaviors and claims Mr. Leininger attributes to James, especially in Soul Survivor. Item (2) in the CSD chronology states that James had nightmares of being in a plane that bursts into flames after being shot. The video is explanatorily relevant, if not an obvious source influencing the emergence and character of James’s nightmares. The video contains the imagery of the nightmares, as well as an aspect of the nightmare’s narrative. And James started watching the video just before his nightmares began, and he continued watching it while his nightmares were recurring for nearly a year. And it needs to emphasized that he repeatedly watched the video as a ritual of sorts, so much so that the VHS tape had to be replaced at least twice (SS, pp. 21-22, 24, 57 118). The video is also potentially relevant to other items in the CSD chronology – for example, (3), (6), (7), and possibly (14), (16), and (20).

A video clip of the combat strike scene is below. For screen shots of these and other video images, see my page Blue Angels: Around the World at the Speed of Sound.

Video: Combat Strike Scene in Blue Angels Video

Little James watched the above clip over and over again for more than a year. He starting watching it before his nightmares began. And he continued watching it while his nightmares were ongoing for nearly a year.

Consider also how Mr. Leininger’s writing Carol Bowman out of his chronology impacts crucial item (13) in his list of alleged evidence.

13) Est. Date 1 September 2001 – While playing with an airplane in the sunroom, James stood up and saluted saying “I salute you and I’ll never forget. Now here goes my neck.” During the same play period he spontaneously said “Before I was born, I was a pilot and my airplane got shot in the engine and crashed inthe water and that’s how I died.” (CSD, p. 12)

According to Bowman and the Leininger narrative in Soul Survivor, Bowman got involved in the case in winter 2001. At that time she told the Leiningers that James was recalling a past life in his nightmares. She also advised them to tell James that he was experiencing things that had happened to him before. She told them this in February 2001 and they followed her advice. Given this, it’s unsurprising that James would later embed claims in a first-person reincarnation narrative. Cutting Bowman from the chronology masks this obvious naturalistic inference.

Nor is Mr. Leininger’s failure to detect ordinary sources of information restricted to the first two years of the story. It extends to later claims he attributes to his son.

Some of these are blatant.

30) 7 October 2003 – Out for a walk on my birthday with James I was talking about the tough day I’d had. James said “Dad, every day is like a carrier landing. If you walk away from it you are OK!” Again, this was not a 5-year-old child speaking; it was an older soul. (CSD, p. 16)

James’s philosophical insight here has a fairly obvious ordinary source which apparently didn’t show up on Bruce Leininger’s radar. James’s statement is found in a 2002 A&E documentary on the Corsair plane. In Battle Stations: Corsair Pacific Warrior, WW2 Corsair pilot Colonel Archie Donahue said, “Each day in life is like a carrier landing. If you can walk away from it, you’re in good shape.” The A&E documentary focused on the role of the Corsair in the war in the Pacific. Donahue made his statement while discussing difficulties of carrier landings.

Video: Archie Donahue Statement in Corsair Pacific Warrior

We know James saw this documentary. It’s the “History Channel program about Corsairs” the Leiningers admit James watched on a video tape (SS, p. 268). The Leiningers don’t give the title of the video. However, they describe a scene uniquely characteristic of the program. So, there’s no doubt they’re referring to the Battle Stations Corsair film.

Although the Leiningers are not clear about when James watched the tape of the program, we can establish a time frame. The documentary first aired on December 26, 2002 on the History Channel network. James made the statement to his father on October 7, 2003. So, James had nine months to acquire a tape of the program, watch it repeatedly, and absorb its content.

The statement Mr. Leininger invests with great evidential value appears in this program. Yet, he doesn’t as much as acknowledge this fact. He exhibits no awareness of it. He admits the family had a tape of the program. He acknowledges that James watched it. But he’s unaware of the information James mined from the video. What Mr. Leininger regards as evidence for reincarnation is nothing of the sort. It’s evidence for how easy it is for children to pick up information without their parents noticing.

Premise (P4) – Coincidence

Mr. Leininger also dismisses the role of coincidence in the James Leininger story. But he does so in the absence of any kind of argument. He just asserts that the facts go “beyond coincidence.” There’s not even an attempt to show this. It’s just his impression, a description of his psychology.

This is understandable from one angle. It’s fairly well-established that ordinary intuitions concerning probability are frequently incorrect. People are poor judges about how probability governs events in the world. Consequently, they don’t reason well about coincidences. This is especially true when it comes to reasoning about the paranormal. Leininger illustrates many of these wrongheaded intuitions.

Supposedly, the facts in the Leininger case are too improbable for chance to have played a role. But what is this degree of improbability (even approximately)? And how improbable must an event be to plausibly rule out coincidence? In the 1980s Evelyn Marie Adams won the New Jersey lottery twice in four months. The chance of that happening was 1 in 1 trillion. Is the improbability of any fact in the James Leininger story greater or less than that? If greater, Mr. Leininger should show how he determined that probability. If less, then something more improbable than the Leininger story happened by chance.

But suppose that a hypothesis, like coincidence, confers a low probability on some observation(s). Why should that be a reason to reject the hypothesis? Why should it be evidence against the hypothesis? I draw an Ace of Spades from a deck of cards. If it was a normal deck and a random draw, that outcome has a probability of 1/52. The draw is improbable. Surely my drawing the Ace of Spades is not evidence against the draw being random. Nor is it evidence against the deck being a normal deck. And it’s reasonable to think the New Jersey lottery was fair, despite Adams’ two wins being hugely improbable. The moral of the story: you don’t reject a hypothesis merely because it makes some observation(s) improbable. Of course, perhaps such a hypothesis is false. Then again, maybe something improbable happened.

What is relevant is whether hypothesis H1 makes an observation more or less probable than does hypothesis H2. In that case, we can say the observation is evidence for or against a particular hypothesis. If observation O is more probable if H1 is true than if H2 is true, O favors H1. But this is contrastive. You contrast what each of two hypotheses leads you to expect. From this viewpoint, it doesn’t matter how improbable coincidence makes an observation. What matters is whether the reincarnation hypothesis makes the observation less improbable than does coincidence. Showing that, of course, is considerably more difficult than just saying it’s so.

Of course, there are other probabilistic errors that vitiate Mr. Leininger’s thinking. For example, many of his alleged matches depend on the law of near enough. He regards sufficiently similar events as identical. For example, the content of James’s dreams and the circumstances of Huston’s death. This kind of problem is rampant in pro-reincarnation literature. It’s a glaring weakness, though. Yet, survivalists like Leininger continue to fall into this trap because they ask the wrong kinds of questions. They ask whether a subject’s claims fit a fact. Instead, they should ask what other facts would also fit the subject’s claims. This will tell you how broad or narrow the parameters of a match are. That’s a helpful way of seeing whether you’re relying on the law of near enough to create illusory matches.

See section 7 of my JSE paper for a detailed application of the improbability principle to various aspects of the James Leininger case. For the broader conceptual landscape, see David Hand’s The Improbability Principle and Leonard Mlodinow’s The Drunkard’s Walk.

But there’s a more pedestrian fallacy lurking in Mr. Leininger’s discussion. And it requires no sophisticated grasp of the law-like features of the world. Just because it seems to Mr. Leininger that the presumed facts go “beyond coincidence,” that’s absolutely no reason to think that they do. And just because Mr. Leininger can’t imagine an ordinary source of explanation, that’s no reason to think something extraordinary influenced James’s experience, behavior, or claims. These closely-allied errors in critical thinking – a variant on the appeal to ignorance – vitiate Leininger’s BICS essay, and much of the literature on survival.

(P4) is nothing more than an unsupported assertion. And we know it’s false. That’s not to say it’s not evidence. It is evidence – it’s evidence of the limits of Mr. Leininger’s knowledge. But it’s no evidence for the truth of Mr. Leininger’s reincarnation hypothesis.

What about the Rest of the Evidence?

Mr. Leininger’s CSD “chronological trail” contains a list of 45 items. 34 are items involving attributions of claims and behaviors to James, and 11 are descriptions of confirmatory evidence. Of the 34 James attributions, I have addressed the dubious nature of 14 of them as evidence for reincarnation: (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6 – partial), (7 – partial), (8), (12), (13), (14), (16), (20), and (30). Obviously, I’ve not addressed all of the items in Leininger’s chronology. Thankfully, it’s not necessary for me to do so.

First, I’ve tried to show several ways in which Mr. Leininger’s argument is defective. None of my counter-arguments requires addressing every item in his list of purported evidence, nor even most of them. Mr. Leininger nowhere shows that his conclusion – James Leininger is the reincarnation of James Huston, Jr. – is a necessary inference from the presumed facts he catalogues. Much less does he show that his reasoning carries the force of a geometric demonstration. He fails to do this because he fails to present any argument at all. The rest of the alleged evidence is irrelevant to this. His reasoning also relies on unwarranted claims – they’re either false or we have good reason to doubt that they’re true. Showing this doesn’t require that I address every item in his list.

To make this clear, let’s consider the more plausible version of Leininger’s suggested argument.

(P1) James made the claims attributed to him in the chronology and made them at the times specified in the chronology.

(P2) James exhibited the behaviors attributed to him in the chronology and exhibited them at the times specified in the chronology.

(P3) All the claims and behaviors attributed to James in (P1) and (P2) exactly match James Huston, Jr.

(P4*) It is improbable that the matches in (P3) are mere coincidences or that James acquired the information from ordinary sources.

Therefore, probably:

(C) James Leininger is the reincarnation of James Huston, Jr.

I’ve shown that (P3) is false. It’s easily refutable by a single counter-example, but I’ve provided several. I’ve also shown that the no-ordinary-source-of-information component of (P4) is false. And Leininger provides no evidence that would rule out (as improbable) the mere coincidence component of (P4). So we’re not warranted in accepting (P4) either. I’ve also shown that Mr. Leininger has a credibility problem. This prevents us from rationally accepting premises (P1) and (P2). Inconsistencies within and between the various chronologies and suspicious narrative redactions are a serious problem in this case. Mr. Leininger can’t be trusted to accurately convey what James said/did and when he said/did it. If even one premise in the above argument is unwarranted, the argument is defeated. I’ve shown that each of the four premises is unwarranted. This is not simply a weak argument. It’s textbook terrible.

Second, I’ve intended this discussion to be a supplement to my lengthy JSE paper. For that purpose, it’s not necessary to address other items in the CSD chronology. Of course, in my JSE paper I address some of the more interesting items not discussed here. These include the Natoma and Jack Larsen claims attributed to James Leininger in late summer/early fall 2000. What I have to say about these items is important. Among other things, I address widespread confusions about how coincidence and improbability work in the world. I’d encourage people to read my detailed JSE report to see what I have to say about these other aspects of this case.

How Unreliability Infects Other Alleged Evidence

Some survivalists are likely to respond that, in the absence of addressing the other items in Leininger’s chronology, skepticism about the case as a whole is not warranted. I’m afraid this isn’t plausible. Some of the items discussed here and in my JSE paper are essential features of the case as a whole. So, it’s not as if the dubious nature of these items has no relevance to what we think of the case as a whole. Quite the contrary. But more importantly, the rest of the evidence is only as credible as Mr. Leininger is reliable. And that’s a serious problem for this case.

Suppose we acquire good reasons to doubt the reliability of a source. All other things been equal, we have acquired good reasons to doubt whatever they say. Showing that some of a person’s testimonial claims are false may be necessary to establish their lack of reliability, but skepticism concerning the rest of their claims doesn’t require showing that their other claims are false.

Neither Bruce nor Andrea Leininger is reliable when it comes to what James said/did or when he said/did it. And they’re even less reliable when it comes to ruling out the plausibility of ordinary sources of information. Appealing to the rest of the evidence requires trusting testimony that should not be trusted, especially when it comes to judgments about James’s exposure to ordinary sources of information. Even if we could trust Mr. Leininger’s chronology of facts, we simply cannot trust him in ruling out ordinary sources of information.

Bob Greenwalt and the Three G.I. Joes

Let me illustrate why the latter point is significant to the evidential force of other alleged facts in the case. I’ll use two items from Leininger’s list which some people seem to find particularly impressive.

I. Item (36) (CSD, p. 17) describes an incident on September 11, 2004 at the Natoma Bay reunion in San Antonio Texas which James Leininger (then age six) attended. It concerns a meeting between James Leininger and WW2 veteran Bob Greenwalt. Greenwalt was a pilot in Huston’s VC-81 squadron and who flew with Huston on the mission in which Huston was killed. Greenwalt reportedly stepped out of the elevator, saw little James, and said to him, “Bet you don’t know who I am.” James reportedly responded, “You’re Bob Greenwalt.” Later the Leiningers asked James how he knew the man was Greenwalt and he said, “I remembered his voice.”

II. Items (11), (15), and (33) concern James’s allegedly giving his G.I. Joes names that matched the names of friends of James Huston and who served with him on the Natoma Bay as members of the VC-81 flight squadron but who died in WW2 before Huston was killed. We’re told that on April 10, 2001 James received a G.I. Joe with brown hair for his birthday and named it Billy – item (11). Then on December 25, 2001 James received a G.I. Joe with blond hair for Christmas and named it Leon – item (15). Finally, on December 25, 2003, James received a red-haired G.I. Joe for Christmas and named it Walter – item (33). As Mr. Leininger explains, Billy Peeler, Leon Conner, and Walter Devlin served with Huston in his flight squadron on the Natoma Bay, and James Leininger allegedly told his parents these men met him (as Huston) when he got to heaven (CSD, pp. 11-12, 16).

The Consequences of Unreliable Testimony

Like so many of the other items in Leininger’s chronology, (I) and (II) will provide evidential support for the reincarnation hypothesis only if:

(*) Bruce Leininger can provide a reasonable assurance that James was not exposed to anything that could be a salient information source.

More specifically, the evidential force of (I) and (II) depends on our being warranted in accepting (*). But we’re not.

Now consider the implications of this for the assessment of (I) and (II). Consider just how problematic it is that we can’t rationally accept (*).

According to Soul Survivor (SS, pp. 269-270), though not included in CSD, Bob Greenwalt called the Leininger residence shortly after the airing of the April 2004 ABC Primetime episode. This would’ve been a few months before the Natoma Bay reunion James attended. Andrea Leininger picked up the phone and said out loud “Bob Greenwalt is on the line – he knew James Huston” (SS, p. 269). Bruce Leininger then got on the phone and the two talked like old war buddies.

If James was present, he would’ve heard Bob Greenwalt’s name mentioned. If he was near the phone, he could’ve easily heard Bob Greenwalt’s voice coming through the phone. For all we know, the Leiningers had two lines. In which case, James could’ve easily heard Greenwalt’s voice by picking up the other line. For all we know, this wasn’t the only time Greenwalt called the Leininger residence. And for all we know, James heard Greenwalt’s name and voice at the Natoma Bay reunion before the elevator encounter. None of these scenarios is antecedently improbable. The only people who can give us a reasonable assurance that these scenarios were unlikely are the Leiningers. But these are the same people who couldn’t detect James’s exposure to images and information on videos he regularly watched. They are the same people who, despite their best efforts, couldn’t trace anything James said to the Cavanaugh Flight Museum.

As for the G.I. story, James named the G.I. Joes on April 10, 2001 (Billy), December 25, 2001 (Leon), and December 25, 2003 (Walter). The three events are spread out over 20 months. Can we be reasonably sure that nothing James learned influenced the naming of the G.I. Joes? What could possibly have so influenced him? On January 6, 2001 (CSD, p. 11), Bruce Leininger acquired a list of 18 Natoma Bay men killed in action during in WW2. The list included James Huston, Walter Devlin, and Leon Conner. Three other Natoma Bay veterans, including Billie Peeler, were not on the list Bruce Leininger acquired in January 2001, but he subsequently added them based on information he acquired at the Natoma Bay reunion in fall 2002.

As in the case of the Bob Greenwalt story, it’s what we don’t know that matters. Mr. Leininger was deeply involved in doing historical research to validate his son’s claims. Did Mr. Leininger never mention any of the names of these names out loud over 20 months? Could James have heard any of these names in that way? At some point during the 20 months, James began to read. Did James have access to the KIA list, including the names of Leon and Walter, at any point prior to Christmas 2001 or Christmas 2003? There are many conceivable causal pathways, and many more that wouldn’t immediately come to mind. Only the Leiningers can give us reasonable assurance that James didn’t pick up on these names by hearing or reading them. But this they cannot do since they’ve demonstrated themselves to be unreliable in detecting fairly obvious sources of information that influenced James.

The problem should be apparent. What James said/did and when he said/did it is only one area where the reliability of Mr. Leininger is important. It also matters whether we can trust his judgment (and Andrea Leininger’s judgment) concerning ordinary sources of information. Skepticism about (I) and (II) doesn’t require proving that James acquired the salient information in any of the above scenarios. It’s sufficient to have good reason not to trust that Mr. Leininger can plausibly rule out such scenarios.

Some advocates of reincarnation may double down on Mr. Leininger’s credibility. However, they should be prepared to state just how much outright falsehood, factual gerrymandering, and narrative shenanigans are acceptable or tolerable in the interest of defending the evidential value of this case.

Conclusion: Masking the Fundamental Question

Does Bruce Leininger’s CSD essay provide the “best evidence” for survival? Nothing I’ve said here implies that it doesn’t. Perhaps the judges in the Bigelow competition were right and this paper is an example of the best survivalists have to offer in the way of evidence for their assertions. But if that’s the case, the judges have provided a stunning validation of just how impoverished the field of survival research is. If Mr. Leininger’s essay is among the best survivalists have to offer, they’ll need to considerably up their game. And seeing as several other prize-winning essays in the competition favorably refer to this case, I’d say the wider pool of winners reinforce rather than obviate this worry.

Then again, the central question to which essayists responded in the BICS competition already betrays confusion. The “best evidence” can be and often is bad evidence. Sometimes it’s downright shitty evidence. The better question is, what is good evidence? And to answer this, we should probably first get clear about what isn’t good evidence. Weak inferences from unwarranted premises is certainly one example of really bad evidence.

But the question of evidence – good or bad – is perhaps premature. As H.H. Price pointed out over half a century ago, before we ask about the evidence for survival, we should first be clear about the meaning of survival itself.

I would suggest that those who incline to the Survival hypothesis should spend less of their time collecting evidence for it, and should rather turn their attention for the present to the clarification of the hypothesis itself. (H.H. Price, Philosophical Interactions with Parapsychology, p. 25).

Price was well-versed in the alleged empirical evidence for survival in his day, but he was also a philosopher and so understood the conceptual dimensions to the survival debate. And he was right about the misguided and premature emphasis on getting evidence for an ill-defined hypothesis, especially one that comes married to a variety of unspoken assumptions. C.D. Broad also emphasized this point. In more recent years, Stephen Braude has emphasized the importance of the conceptual scaffolding of the survival debate. It was an important theme in his book Immortal Remains, and he also discussed it in his prize-winning essay for the BICS competition (quoted above). It was also a crucial part of the argument I presented in my 2016 book on empirical arguments for survival.

The reason why the conceptual questions are important is that how we answer questions of evidence depends on them. These questions include epistemological questions about the nature of evidence, probability, and explanation. But the content of the survival hypothesis is central. Until we get clear about that, we won’t know how the world should look if our hypothesis is true or how it should look if our hypothesis is false. We won’t know whether life after death has any empirical consequences at all. So, unless we get clear about the concept of life after death, we won’t be clear about what favorable evidence for it should even look like it. And we won’t be clear about the kinds of assumptions such favorable evidence requires.

If we wish to have an empirically meaningful hypothesis, we can neither dispense with nor retard inquiry into the concept of life after death itself. If we fail here, we’re likely to be confident that the best evidence is good evidence, when in fact it may be shitty evidence or no evidence at all.

Dr. Michael Sudduth

Revised: 1/18/2022

Follow

Follow